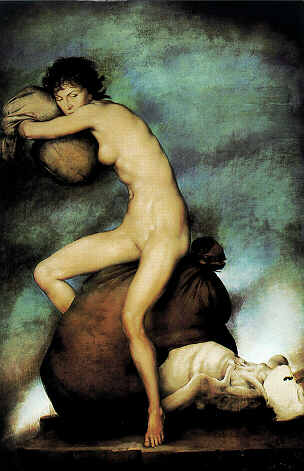

A cold white light illuminates the tragic twilight from below.

Avarice, the she-wolf who "molte genti fe’ giÓ viver grame" (made many people live wretchedly) tightly clasps the bag of her treasure to her breast making a pillow of it. Hand and face contracted into a continuous and terrible grimacing effort of possession. She sits on an even larger bag in precarious balance, almost clutching it between her legs, not realising she is crushing a faceless corpse, the apocalyptic emblem of the poverty of others, the ultimate wreck washed up to her by the vast ocean of hunger which devours thousands of skeletal, pot-bellied men, women and children every day. The air seems to echo with their endless wails.

Like a "lupa... carca nella sua magrezza" (she-wolf ... burdened by its thinness) or "usura che offende la divina bontade" (usury that offends divine benevolence), the woman clutches her treasure, anxious not to lose it but to make it grow, so the shadow clutches at her body and strips the flesh off her shapes. The angled and bowed glance cannot see. It is blinded - as Cyprian wrote - by a thick deep fog of avarice which deprives her of any splendour of truth. Her face is impassive. Her long slim body is exaggeratedly thin; her long, thin legs, sinewy like her foot, with only its tip resting on the ground.

It is all too easy to see in the two large bags a reference to those rocks which in Hell the miserly people push with their breasts, looked down on by Dante with cold disdain, reduced as they are to pure matter in movement having hidden their souls in matter itself.